I am so excited to bring you this guest post by paediatric allergy doctor, Dr Jose Costa! Weaning can be a confusing and worrying time, especially if your baby or someone in your family already has an allergy. I know you have so many questions about weaning - from when to start weaning, and which babies are at high risk of developing an allergy, to when and how to introduce allergens to a baby. Today Dr Costa shares his expert opinion with us on all these topics and more in this in-depth article.

Before we get to the practical stuff, Dr Costa also covers the historical and cultural context of weaning. Why is this important? Well, weaning practices have changed massively throughout history. Knowing this helps to give us a little bit of perspective. There are so many different weaning practices from different eras and cultures - and the human race has continued to survive and thrive through all of them! It's really worth taking the time to understand this at a time where there is so much anxiety around the 'right' way to introduce solid foods to babies. So grab a cup of tea and let's dive in!

To Wean or Not to Wean?

The importance of feeding is part of human life from the day we are born.

For the first few months, babies are only able to taste sweet and sour, leading to their first choice favouring the sweet taste of mother’s milk. Eventually, at around 6 months, the taste buds develop further. The baby's palate becomes more sensitive not only to tastes but also to textures.

Naturally the first, and nutritionally complete food, will be breast milk, with exceptions for those that either by choice or physiological reasons are formula fed. This will carry on until around 6 months of age, at which point solids should be introduced.

Why is there such a need to change into solids, decreasing the need for milk? That need is mainly, not only, to growth associated nutritional needs, but also focused on allergy prevention1, 3, 4, 6.

But weaning and the age that is done, is not just influenced by those needs but also by a wide variety of beliefs, personal choices, historical background or, with that being the most comparable link between developed and underdeveloped world, the need to go back to work16, 17.

So what can history teach us about feeding babies and weaning?

Historical Background of Weaning

Breast feeding is so much engrossed in our lives, that for millennia our civilization has been depicting it in so many sources. From early old Babylonian statues (circa 2,300 BC) [Image 1], passing through old Egypt with statues of Princess Soberknakht (1,700 to after 1,630 BC)11 to ceramic vessels made by the Moche artisans from Peru (1-800 AD) 10, all showing breast feeding mothers and their babies.

Author Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP (Glasg)

We don't know a great deal about what babies were fed throughout the Middle Ages, there is evidence that wealthier women did not breastfeed their children12. The use of “wet nurses” (a lactating woman that breastfeeds the children of others) was common and carried until our era, where it is still seen in some societies, though highly controversial due to the potential transmission of diseases.

During these times, some children were also fed either animal milk or pap (a soft paste or a porridge), using for that effect an “infant cup” or a “pap feeder” (a container similar to a beaker cup), respectively. The greatest challenge was the cleaning of such cups, often harbouring harmful bacteria, but also the poor nutritional content of those foods9.

Due to that, somewhere in the 19th Century, people turned to glass as the preferred container for baby milk, as it was clear and easier to clean. Interestingly, some companies started to develop commercial formulas around this time. Unfortunately breastfeeding then declined in popularity, until its resurgence towards the middle of the 20th Century12.

Introduction of Commercial Formulas

It is likely that Mead Johnson was the first to release a formula, with this happening around 1912, mainly as a milk additive and composed of maltose and dextrin (called Dextri-Maltose). This could only be given by Physicians, so it was also the first medically prescribed formula.

Saying this, records show that Henri Nestlé started working on his Infant Formula in 1867, putting to sale in the Swiss Town of Vevey around the same time13.

Around the same period that Dextri-Maltose was released, several other formulas also came onto the market, with the abbreviations of their names lasting up to now. For example, SMA (simulated milk adapted), Similac (similar to lactation) or Enfamil (infant meal).

Past advice on Starting Solids

In the first two decades of the 20th Century, children were not offered solids until their first year, as it was thought it could harm the child. In contrast, soon after that the advice was reversed and children were then offered solids, including meat and liver, in the first two weeks of life. Cereals were to follow and between 6 and 9 months of age vegetables should be given6.

It is important to note the role of baby formula has, even now, as there is a significant decrease of breastfeeding after the first month of life. This might also be the reason so many mothers decide to start weaning at an earlier age [Table 1].

| England | Wales | Scotland | N Ireland | UK | |

| Birth | 66 | 58 | 61 | 55 | 65 |

| 1 week | 46 | 38 | 42 | 35 | 45 |

| 2 weeks | 39 | 32 | 37 | 31 | 38 |

| 3 weeks | 34 | 28 | 32 | 25 | 33 |

| 4 weeks | 29 | 21 | 25 | 20 | 28 |

| 6 weeks | 22 | 15 | 19 | 13 | 21 |

| 2 months (8 weeks) | 18 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 18 |

| 3 months (13 weeks) | 14 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 13 |

| 4 months (17 weeks) | 8 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 7 |

| 5 months (21 weeks) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 months (26 weeks) | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

Table 1

Prevalence (%) of exclusive breastfeeding by country

(2005 national Infant Feeding Survey)

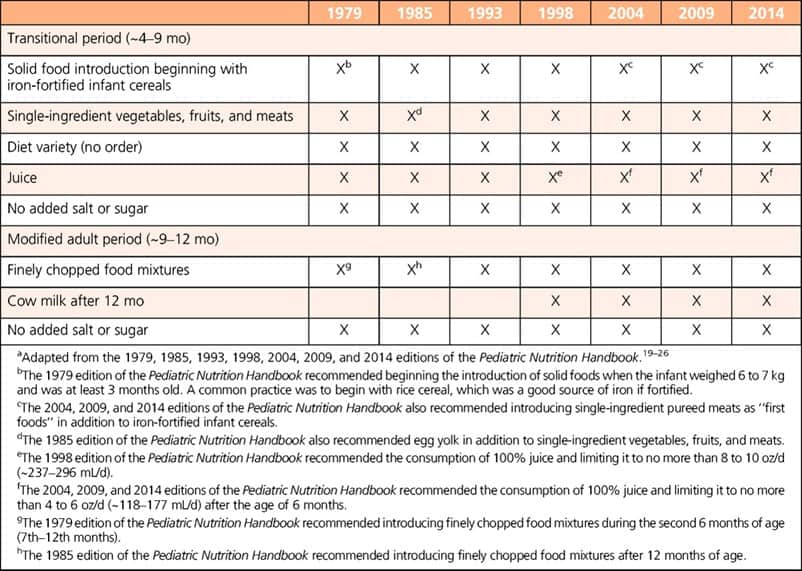

Though solids have been given from very early stages in babies’ lives, there is not so much emphasis on its discussion, apart from more recent studies, which show the variations mainly in the 20th Century [Table 2].

However, we have a better undesrtanding of certain habits that still keep going up to now.

Premastication

We don't exactly know when it started, but we suspect that premastication began with the onset of humankind.

Writings traced back to ancient Egypt are the first known evidence of its existence, with some description of how it was done14.

But what is it?

Premastication, pre-chewing, or kiss feeding, is the act of chewing food for the purpose of physically breaking it down in order to feed another that is incapable of masticating the food by themselves8.

This meant that solids could be introduced early as the first few weeks of life.

Due to this subject being so controversial, I will address the main reasons for why it is done and by whom.

Why do some cultures use premastication?

The explanations for this varies, depending on the ethnographical studies.

Reasons like nutrition, disease prevention, disease healing, and cultural and spiritual beliefs 5.

Zhang, on his thesis, says that “in 31 out of 39 cultures, premastication is solely for providing foods for babies. In 4 cultures, babies and young children were given certain kind of premasticated food for a beneficial outcome that originated in religious and cultural beliefs. In two cultures, people premasticated medicine (herbs) for infants to cure disease, and in one culture, to prevent disease. Sometimes there is more than one purpose; for example, for the Garo (Tibeto-Burman ethnic group), the purpose for premastication is both for nutrition and for a beneficial outcome related to a cultural belief”8.

Several studies done on the highlander people from north Thailand, the “Chao Khao”, have shown an example of the economical reasons for this practice. Mothers often need to travel to places far from where they live in order to work, not being able to either bring their babies or go home to feed them. As such they are left with elderly women at the village, who feed them, often premasticating food to give babies16, 17.

What is interesting is that this practice still happens on all continents, including Europe and North America. In most cases this is due to people migrating from countries where this practice still exists.

Naturally it comes with pros and cons to it, and we'll take a look at these next.

Pros and cons of premastication

The natural risk of disease transmission, not only associated with poor oral health of the person premasticating, but also of virus (like Hepatitis B or HIV) or bacteria they might carry, are the main worry15.

Nutritional deficiency and the associated staggered growth is commonly another reason for criticising this way of feeding babies. We also need to consider that the process of ingesting pasty foods is more complex than the swallowing of liquids, leading to further problems including the increased risks of choking.

Nonetheless there are some benefits to it as well.

Some studies have shown it might be useful when appropriate foods for babies are either not available or they are costly, or even there is no availability of supplements to give to babies, mainly iron.

There is also some evidence saying that IgA present in saliva, could transfer to the baby and due to its bacteria-killing properties, might be beneficial15.

Current weaning advice:

There is much dispute around the age at which weaning should start. One of the reasons being gut maturity6, 7.

There has been some media attention on a piece of research in JAMA paediatrics that implied that babies who have solids introduced before 6 months sleep better. UNICEF has looked at this research and they have released a statement identifying weaknesses in this research, in particular potential bias in reporting. They continue to recommend that solids are not introduced until 6 months3, 18.

UNICEF also states SACN (Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition) refers that “introducing solid foods before four months is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal, respiratory and ear infections in infants” and, as such, continues to advise solids are not introduced until 6 months19.

Unfortunately both UNICEF and SACN have disregarded current advice1, 3, 4 suggesting allergens should be introduced from 4 months of age, with the suggestion that 3 months would also be protective against development of allergies.

So is this good advice? Let's consider the evidence.

Evidence:

- LEAP - Of the children who avoided peanut, 17% developed peanut allergy by the age of 5 years. Remarkably, only 3% of the children who were randomized to eating the peanut snack developed allergy by age 5. Therefore, in high-risk infants, sustained consumption of peanut beginning in the first 11 months of life was highly effective in preventing the development of peanut allergy.

- EAT - The EAT Study has found that introducing allergenic foods into the infant diet from three months may be effective in food allergy prevention when sufficient amounts of allergenic foods are consumed. The study found that the prevention of food allergy could be achieved with weekly consumption of small amounts of allergenic food. This means about 1½ teaspoons of peanut butter and one small boiled egg.

- LEAP-ON - After 12 months of peanut avoidance, only 4.8% of the original peanut consumers were found to be allergic, compared to 18.6% of the original peanut avoiders, a highly significant difference.

- The Government’s own Infant Feeding Survey shows 51% of infants were reported to have received solid foods before 4 months of age. This figure is consistent with the average age of introduction of solids in the Millennium Cohort Study which was 3.8 months2.

- One reason put forward for not introducing solids before six months is concern about an increased risk of gastrointestinal infections. However, the Millennium Cohort Study2 recently found that the age of introduction of solids had no effect on risk of hospitalization for diarrhoea or lower respiratory tract infection.

So where do we stand on weaning?

You should follow current recommendation of introducing solids at 6 months of age.

Children whose older siblings have a food allergy are not at higher risk of developing allergies. They should follow the same advice21.

With the following exceptions, when it should be introduced at 4 months of age1, 3, 4, 20:

- Infants and young children with a family history of atopy, as they are at high risk for developing allergic disease.

- Those with a personal history of atopy, particularly those with moderate-to-severe eczema, are also at increased risk of developing other atopic diseases including food allergies.

- Infants who already have a food allergy.

Weaning Babies with Eczema

If the child has eczema, allergens should only be introduced if the eczema is under control. However, introduction should be delayed and the child referred to a specialist in the following circumstances. The main reason for this is so any skin reactions can be seen and associated with the food being taken21:

- The eczema is uncontrolled.

- Needs 1% Hydrocortisone more often than once a day for 6 weeks.

- Needs a stronger steroid more than once.

Most importantly, if a child has passed the age of 4-6 months and no allergens have been introduced, you should do it at once and do not delay any further.

They should only be seen by an allergist if there is an history of reactions to a particular food. In this case they should be tested and eventually be guided by an allergy dietitian. For the same reason, there is no need for most children to be seen by a dietitian before weaning.

Which foods to introduce first and how to do it?

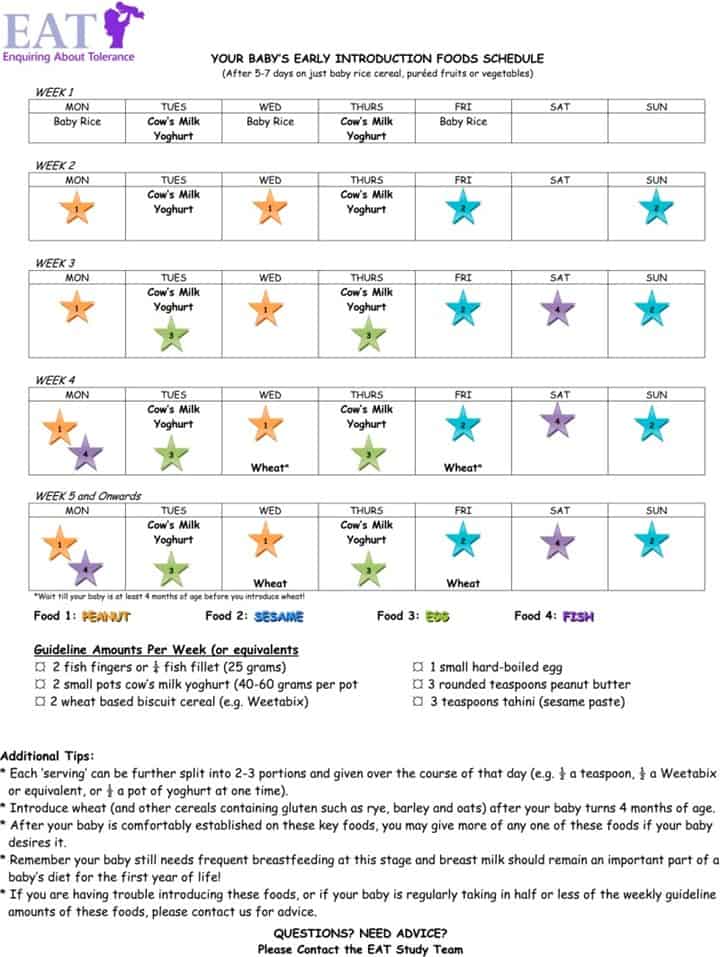

Following several studies, the foods/allergens that should be chosen first are peanut and egg. Those had the highest evidence so far.

Next you can give wheat, sesame (other seeds included) and fish (white and red fish, but seafood can also be included).

No specific studies done for tree nuts, though the suggestion would be to introduce them after wheat, sesame and fish.

Next, let's take a look at the best way to introduce allergens21, 22 [Table 3]:

- Peanuts – use smooth peanut butter, puffed peanut sacks (if under 7 months they should be diluted in water or milk) or grind whole peanuts into a fine powder. It can be mixed into any pureed food the child has already eaten, yoghurts or baby porridge.

- Eggs – either scrambled eggs, omelettes, soft or hardboiled egg. This can be mixed into any pureed food the child has already eaten, yoghurts or baby porridge.

- Sesame or other seeds – hummous, finely ground seeds mixed into any pureed food the child has already eaten, yoghurts or baby porridge.

- Wheat – weetabix or similar cereal, well cooked pasta, toast fingers or couscous.

- Fish or seafood – very well cooked and mashed. It either can be eaten on its own or mixed into any pureed food the child has already eaten.

- Tree nuts – finely ground and mixed into any pureed food the child has already eaten, yoghurts or baby porridge. If you find a butter, you can also use it.

- Milk – sugar free yoghurt, fromage frais or whole milk mixed in porridge or mashed potato. This should only be from around 7 months of age (though it was introduced earlier in the EAT study).

Weaning Warnings:

The initial dose should be roughly ⅛ or ¼ of a normal dose, followed by increased doses starting the next day.

Once safely introduced, the aim would be to have that allergen at least once per week.

You should not introduce more than one new allergen at a time. As there is a potential risk (though extremely small) that a delayed reaction can occur more than 24 hours later, it would be safe to say that a new allergen can be safely introduced 3 days after the previous one.

If at any point you suspect an allergic reaction, stop giving that food immediately, give anti-histamines and/or call the emergency services. In this case, your child needs a referral to the allergy services so he/she can be tested. Eventually you may need to do either a food challenge or a careful reintroduction of the allergen at home again.

References:

- LEAP Study (Lack et al., Dec06 – May09)

- Millennium Cohort Study (Quigley, 2008 - present)

- EAT Study (Lack and al., Jan08 – Aug15)

- LEAP-ON Study (Lack et al., May11 – May14)

- Infant and young child complementary feeding among Indigenous Peoples: Grace S. Marquis, Susannah Juteau, Hilary M., Creed-Kanashiro, Marion L. Roche

- Historical Overview of Transitional Feeding Recommendations and Vegetable Feeding Practices for Infants and Young Children: Nutr Today. 2016 Jan; 51(1): 7–13.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. In:Pediatric Nutrition Handbook. (editions from 1979 to 2014)

- Zhang, Yuanyuan (May 2007),"The role of pre-mastication in the evolution of complementary feeding strategies: a bio-cultural analysis", Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Honors Theses

- Sweet and Clean - A Glance at the History of Infant Feeding: Dr. Ruth M. W. Moskop and Melissa M. Nasea. ar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

- Larco Hoyle, Rafael. Los Mochicas. Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera 2001.

- Image displayed at the Brooklin Museum

- Riordan, J; Countryman, BA (July–August 1980), "Basics of breastfeeding. Part I: Infant feeding patterns past and present.", JOGN Nursing, 9 (4): 207–210,

- From Pharmacist’s Assistant to Founder of the World’s Leading Nutrition, Health and Wellness Company, Nestlé – Abridged Translation after Albert Pfiffner's 1993 German Edition, 2014

- Kirshenbaum, Sheril (Jan 5, 2011), The Science of Kissing: What Our Lips Are Telling Us, Hachette Digital, Inc.

- Article published in https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/magazine/Prechewed-food-is-bad-for-babies-/434746-1386032-r15ldb/index.html

- Breastfeeding and its relation to child nutrition in rural Chiang Mai, Thailand: J Med Assoc Thai. 2003 May; 86(5):415-9.

- Health Workers’ and Villagers’ Perceptions of Young Child Health, Growth Monitoring, and the Role of the Health System in Remote Thailand: Food and Nutrition Bulletin 2018, Vol. 39(4) 536-548

- JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Aug 6;172(8):e180739. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0739. Epub 2018 Aug 6. Association of Early Introduction of Solids With Infant Sleep: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial.

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/feeding-in-the-first-year-of-life-sacn-report

- Timing of Allergenic Food Introduction to the Infant Diet and Risk of Allergic or Autoimmune Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1181-1192. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12623

- BSACI: Early feeding guidance for Health Care Practitioners.

- BSACI: Infant feeding and allergy prevention – Parents.

Dr Jose Costa: Paediatric Allergy Specialist

Instagram: @childrensallergy

Website: thechildrensallergy.co.uk

Weaning Recipes

Check out my favourite dairy-free weaning recipes, as road-tested by my two test subjects victims children!

[…] Weaning can also be complicated by the need to introduce allergens one at time (if that is the advice that you have been given). This can slow things down and take up a lot of additional time and planning. It can also be stressful if your child doesn’t want to eat the target food! If your infant had reflux or vomiting as a symptom of CMPA they may have developed a hypersensitive gag reflex. This means they may be more prone to gagging. You may notice they gag a lot in the early stages of weaning, or that the gagging continues when you may have expected it to diminish. For more information see my blog post on gagging, coughing and choking. […]